Fundamental Value Differences Are Not That Fundamental

July 18, 2018

I

Ozy (and others) talk about fundamental value differences as a barrier to cooperation.

On their model (as I understand it) there are at least two kinds of disagreement. In the first, people share values but disagree about facts. For example, you and I may both want to help the Third World. But you believe foreign aid helps the Third World, and I believe it props up corrupt governments and discourages economic self-sufficiency. We should remain allies while investigating the true effect of foreign aid, after which our disagreement will disappear.

In the second, you and I have fundamentally different values. Perhaps you want to help the Third World, but I believe that a country should only look after its own citizens. In this case there’s nothing to be done. You consider me a heartless monster who wants foreigners to starve, and I consider you a heartless monster who wants to steal from my neighbors to support random people halfway across the world. While we can agree not to have a civil war for pragmatic reasons, we shouldn’t mince words and pretend not to be enemies. Ozy writes (liberally edited, read the original):

From a conservative perspective, I am an incomprehensible moral mutant… however, from my perspective, conservatives are perfectly willing to sacrifice things that actually matter in the world – justice, equality, happiness, an end to suffering – in order to suck up to unjust authority or help the wealthy and undeserving or keep people from having sex lives they think are gross.

There is, I feel, opportunity for compromise. An outright war would be unpleasant for everyone… And yet, fundamentally… it’s not true that conservatives as a group are working for the same goals as I am but simply have different ideas of how to pursue it… my read of the psychological evidence is that, from my value system, about half the country is evil and it is in my self-interest to shame the expression of their values, indoctrinate their children, and work for a future where their values are no longer represented on this Earth. So it goes.

And from the subreddit comment by GCUPokeItWithAStick:

I do think that at a minimum, if you believe that one person’s interests are intrinsically more important than another’s (or as the more sophisticated versions play out, that ethics is agent-relative), then something has gone fundamentally wrong, and this, I think, is the core of the distinction between left and right. Being a rightist in this sense is totally indefensible, and a sign that yes, you should give up on attempting to ascertain any sort of moral truth, because you can’t do it.

I will give this position its due: I agree with the fact/value distinction. I agree it’s conceptually very clear what we’re doing when we try to convince someone with our same values of a factual truth, and confusing and maybe impossible to change someone’s values.

But I think the arguments above are overly simplistic. I think rationalists might be especially susceptible to this kind of thing, because we often use economic models where an agent (or AI) has a given value function (eg “produce paperclips”) which generates its actions. This kind of agent really does lack common ground with another agent whose goal function is different. But humans rarely work like this. And even when they do, it’s rarely in the ways we think. We are far too quick to imagine binary value differences that line up exactly between Us and Them, and far too slow to recognize the complicated and many-scaled pattern of value differences all around us.

Eliezer Yudkowsky writes, in Are Your Enemies Innately Evil?:

On September 11th, 2001, nineteen Muslim males hijacked four jet airliners in a deliberately suicidal effort to hurt the United States of America. Now why do you suppose they might have done that? Because they saw the USA as a beacon of freedom to the world, but were born with a mutant disposition that made them hate freedom?

Realistically, most people don’t construct their life stories with themselves as the villains. Everyone is the hero of their own story. The Enemy’s story, as seen by the Enemy, is not going to make the Enemy look bad. If you try to construe motivations that would make the Enemy look bad, you’ll end up flat wrong about what actually goes on in the Enemy’s mind.

So what was going through the 9/11 hijackers’ minds? How many value differences did they have from us?

It seems totally possible that the hijackers had no value differences from me at all. If I believed in the literal truth of Wahhabi Islam – a factual belief – I might be pretty worried about the sinful atheist West. If I believed that the West’s sinful ways were destroying my religion, and that my religion encoded a uniquely socially beneficial way of life – both factual beliefs – I might want to stop it. And if I believed that a sufficiently spectacular terrorist attack would cause people all around the world to rise up and throw off the shackles of Western oppression – another factual belief – I might be prepared to sacrifice myself for the greater good. If I thought complicated Platonic contracts of cooperation and nonviolence didn’t work – sort of a factual belief – then my morals would no longer restrain me.

But of course maybe the hijackers had a bunch of value differences. Maybe they believed that American lives are worth nothing. Maybe they believed that striking a blow for their homeland is a terminal good, whether or not their homeland is any good or its religion is true. Maybe they believe any act you do in the name of God is automatically okay.

I have no idea how many of these are true. But I would hate to jump to conclusions, and infer from the fact that they crashed two planes that they believe crashing planes is a terminal good. Or infer from someone opposing abortion that they just think oppressing women is a terminal value. Or infer from people committing murder that they believe in murderism, the philosophy that says that murder is good. I think most people err on the side of being too quick to dismiss others as fundamentally different, and that a little charity in assessing their motives can go a long way.

II

But that’s too easy. What about people who didn’t die in self-inflicted plane crashes, and who can just tell us their values? Consider the original example – foreign aid. I’ve heard many isolationists say in no uncertain terms that they believe we should not spend money to foreign countries, and that this is a basic principle and not just a consequence of some factual belief like that foreign countries would waste it. Meanwhile, I know other people who argue that we should treat foreigners exactly the same as our fellow citizens – indeed, that it would be an affront to basic compassion and to the unity of the human race not to do so. Surely this is a strong case for actual value differences?

My only counter to this line of argument is that almost nobody, me included, ever takes it seriously or to its logical conclusion. I have never heard any cosmopolitans seriously endorse the idea that the Medicaid budget should be mostly redirected from the American poor (who are already plenty healthy by world standards) and used to fund clinics in Africa, where a dollar goes much further. Perhaps this is just political expediency, and some would talk more about such a plan if they thought it could pass. But in that case, they should realize that they are very few in number, and that their value difference isn’t just with conservatives but with the overwhelming majority of their friends and their own side.

And if nativist conservatives are laughing right now, I know that some of them have given money to foreign countries affected by natural disasters. Some have even suggested the government do so – when the US government sent resources to Japan to help rescue survivors of the devastating Fukushima tsunami, I didn’t hear anyone talk about how those dollars could better be used at home.

Very few people have consistent values on questions like these. That’s because nobody naturally has principles. People take the unprincipled mishmash of their real opinions, extract principles out of it, and follow those principles. But the average person only does this very weakly, to the point of having principles like “it’s bad when you lie to me, so maybe lying is wrong in general” – and even moral philosophers do it less than a hundred percent and apply their principles inconsistently.

(this isn’t to say those who have consistent principles are necessarily any better grounded. I’ve talked a lot about shifting views of federalism: when the national government was against gay marriage, conservatives supported top-down decision-making at the federal level, and liberals protested for states’ rights. Then when the national government came out in support, conservatives switched to wanting states’ rights and liberals switched to wanting top-down federal decisions. We can imagine some principled liberal who, in 1995, said “It seems to me right now that state rights are good, so I will support them forevermore, even when it hurts my side”. But her belief still would have ended up basically determined by random happenstance; in a world where the government started out supporting gay marriage but switched to oppose it, she would have – and stick to – the opposite principle)

But I’m saying that what principle you verbalize (“I believe we must treat foreigners exactly as our own citizens!”) isn’t actually that interesting. In reality, there’s a wide spectrum of what people will do with foreigners. If we imagine it as a bell curve, the far right end has a tiny number of hyper-consistent people who oppose any government money going abroad unless it directly helps domestic citizens. A little further towards the center we get the people who say they believe this, but will support heroic efforts to rescue Japanese civilians from a tsunami. The bulge in the middle is people who want something like the current level of foreign aid, as long as it goes to sufficiently photogenic children. Further to the left, we get the people I’m having this discussion with, who usually support something like a bit more aid and open borders. And on the far left, we get another handful of hyper-consistent people, who think the US government should redirect the Medicaid budget to Africa.

If you’re at Point N in some bell curve, how far do you have to go before you come to someone with “fundamental value differences” from you? How far do you have to go before someone is inherently your enemy, cannot be debated with, and must be crushed in some kind of fight? If the answer is “any difference at all”, I regret to inform you that the bell curve is continuous; there may not be anyone with exactly the same position as you.

And that’s just the one issue of foreign aid. Imagine a hundred or a thousand such issues, all equally fraught. God help GCU, who goes further and says you’re “indefensible” if you believe any human’s interests are more important than any other’s. Does he (I’ll assume it’s a he) do more to help his wife when she’s sick than he would to help a random stranger? This isn’t meant to be a gotcha, it’s meant to be an example of how we formulate our morality. Person A cares more about his wife than a random person, and also donates some token amount to help the poor in Africa. He dismisses caring about his wife as noise, then extrapolates from the Africa donation to say “we must help all people equally”. Person B also cares more about his wife than a random person, and also donates some token amount to Africa. He dismisses the Africa donation as noise, then extrapolates from his wife to “we must care most about those closest to us”. I’m not saying that how each person frames his moral principle won’t have effects later down the line, but those effects will be the tail wagging the dog. If A and B look at each other and say “I am an everyone-equally-er, you are a people-close-to-you-first-er, we can never truly understand one another, we must be sworn enemies”, they’re putting a whole lot more emphasis on which string of syllables they use to describe their mental processes than really seems warranted.

Why am I making such a big deal of this? Isn’t a gradual continuous value difference still a value difference?

Yes. But I expect that (contra the Moral Foundations idea) both the supposed-nativist and the supposed-cosmopolitan have at least a tiny bit of the instinct toward nativism and the instinct toward cosmopolitanism. They may be suppressing one or the other in order to fit their principles. The nativist might be afraid that if he admitted any instinct toward cosmopolitanism, people could force him to stop volunteering at his community center, because his neighbor’s children are less important than starving Ethiopians and he should be helping them somehow instead. The cosmopolitan might be afraid that if he admitted any instinct toward preferring people close to him, it would justify a jingoistic I’ve-got-mine attitude that thinks of foreigners as subhuman.

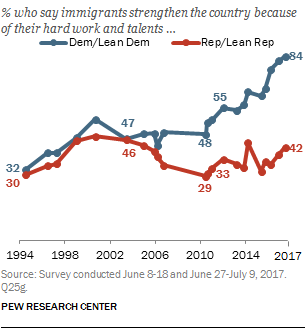

But the idea that they’re inherently different, and neither can understand the other’s appeals or debate each other, is balderdash. A lot of the our-values-are-just-inherently-different talk I’ve heard centers around immigration. Surely liberals must have some sort of strong commitment to the inherent moral value of foreigners if they’re so interested in letting them into the country? Surely conservatives must have some sort of innate natives-first mentality to think they can just lock people out? But…

Okay. I admit this is a question about hard work and talents, which is a factual question. But we both know that you would get basically the same results if you asked “IMMIGRATION GOOD OR BAD?” or “DO IMMIGRANTS HAVE THE SAME RIGHTS TO BE IN THIS COUNTRY AS THE NATIVE BORN?” or whatever. And what we see is that this is totally contingent and dependent on the politics of the moment. Of all those liberals talking about how they can’t possibly comprehend conservatives because being against immigration would just require completely alien values, half of them were anti-immigrant ten years ago. Of all those conservatives talking about how liberals can never be convinced by mere debate because debate can’t cut across fundamental differences, they should try to figure out why their own party was half again as immigrant-friendly in 2002 as in 2010.

I don’t think anyone switched because of anything they learned in a philosophy class. They switched because it became mildly convenient to switch, and they had a bunch of pro-immigrant instincts and anti-immigrant instincts the whole time, so it was easy to switch which words came out of their mouths as soon as it became convenient to do so.

So if the 9/11 hijackers told me they truly placed zero value on American lives, I would at least reserve the possibility that sure, this is something you say when you want to impress your terrorist friends, but that in a crunch – if they saw an anvil about to drop on an American kid and had only a second to push him out of the way – they would end up having some of the same instincts as the rest of us.

III

Is there anyone at all whom I am willing to admit definitely, 100%, in the most real possible way, has different values than I do?

I think so. I remember a debate I had with my ex-girlfriend. Both of us are atheist materialist-computationalist utilitarian rationalist effective altruist liberal-tarians with 99% similar views on every political and social question. On the other hand, it seemed axiomatic to me that it wasn’t morally good/obligatory to create extra happy people (eg have a duty to increase the population from 10,000 to 100,000 people in a way that might eventually create the Repugnant Conclusion), and it seemed equally axiomatic to her that it was morally good/obligatory to do that. We debated this maybe a dozen times throughout our relationship, and although we probably came to understand each other’s position a little more, and came to agree it was a hard problem with some intuitions on both sides, we didn’t come an inch closer to agreement.

I’ve had a few other conversations that ended with me feeling the same way. I may not be the typical Sierra Club member, but I consider myself an environmentalist in the sense of liking the environment and wanting it to be preserved. But I don’t think I value biodiversity for its own sake – if you offered me something useful in exchange for half of all species going extinct – promising that they would all be random snails, or sponges, or some squirrel species that looked exactly like other squirrel species, or otherwise not anything we cared about – I’d take it. If you offered me all charismatic megafauna being relegated to zoos in exchange for lots of well-preserved beautiful forests that people could enjoy whenever they wanted, I would take that one too. I know other people who consider themselves environmentalists who are horrified by this. Some of them agree with me on every single political issue that real people actually debate.

I think these kinds of things are probably real fundamental value difference. But if I’m not sure I have any fundamental value differences with the 9-11 hijackers, and I am sure I have one with one of the people I’m closest to in the entire world, how big a deal is it, exactly? The world isn’t made of Our Tribe with our fundamental values and That Tribe There with their fundamental values. It’s made of a giant mishmash of provisional things that solidify into values at some point but can be unsolidified by random chance or temporary advantage, and everyone probably has a couple unexplored value differences and unexpected value similarities with everyone else.

This means that trying to use shaming and indoctrination to settle value differences is going to be harder than you think. Successfully defeat the people on the other side of the One Great Binary Value Divide That Separates Us Into Two Clear Groups, and you’re going to notice you still have some value differences with your allies (if you don’t now, you will in ten years, when the political calculus changes slightly and their deepest ethical beliefs become totally different). Beat your allies, and you and the subset of remaining allies will still have value differences. It’s value differences all the way down. You will have an infinite number of fights, and you’re sure to lose some of them. Have you considered getting principles and using asymmetric weapons?

I’m not saying you don’t have to fight for your values. The foreign aid budget still has to be some specific number, and if your explicitly-endorsed principles disagree with someone else’s explicitly-endorsed principles, then you’ve got to fight them to determine what it is.

But “remember, liberals and conservatives have fundamental value differences, so they are two tribes that can’t coexist” is the wrong message. “Remember, everyone has weak and malleable value differences with everyone else, and maybe a few more fundamental ones though it’s hard to tell, and neither type necessarily line up with tribes at all, so they had damn well better learn to coexist” is more like it.