[REPOST] The Non-Libertarian FAQ

February 22, 2017

This is a repost of the Non-Libertarian FAQ (aka “Why I Hate Your Freedom”), which I wrote about five years ago and which used to be hosted on my website. It no longer completely reflects my current views. I don’t think I’ve switched to believing anything on here is outright false, but I’ve moved on to different ways of thinking about certain areas. I’m reposting it by popular request and for historical interest only. I’ve made some very small updates, mostly listing rebuttals that came out over the past few years. I haven’t updated the statistics and everything is accurate as of several years ago. I seem to have lost the sources of my images, and I’m sorry; if I’ve used an image of yours, please let me know and I’ll cite you.

Contents

Introduction

0.1: Are you a statist?

No.

Imagine a hypothetical country split between the “tallists”, who think only tall people should have political power, and the “shortists”, who believe such power should be reserved for the short.

If we met a tallist, we’d believe she was silly – but not because we favor the shortists instead. We’d oppose the tallists because we think the whole dichotomy is stupid – we should elect people based on qualities like their intelligence and leadership and morality. Knowing someone’s height isn’t enough to determine whether they’d be a good leader or not.

Declaring any non-libertarian to be a statist is as silly as declaring any non-tallist to be a shortist. Just as we can judge leaders on their merits and not on their height, so people can judge policies on their merits and not just on whether they increase or decrease the size of the state.

There are some people who legitimately believe that a policy’s effect on the size of the state is so closely linked to its effectiveness that these two things are not worth distinguishing, and so one can be certain of a policy’s greater effectiveness merely because it seems more libertarian and less statist than the alternative. Most of the rest of this FAQ will be an attempt to disprove this idea and assert that no, you really do have to judge the individual policy on its merits.

0.2: Do you hate libertarianism?

No.

To many people, libertarianism is a reaction against an over-regulated society, and an attempt to spread the word that some seemingly intractable problems can be solved by a hands-off approach. Many libertarians have made excellent arguments for why certain libertarian policies are the best options, and I agree with many of them. I think this kind of libertarianism is a valuable strain of political thought that deserves more attention, and I have no quarrel whatsoever with it and find myself leaning more and more in that direction myself.

However, there’s a certain more aggressive, very American strain of libertarianism with which I do have a quarrel. This is the strain which, rather than analyzing specific policies and often deciding a more laissez-faire approach is best, starts with the tenet that government can do no right and private industry can do no wrong and uses this faith in place of more careful analysis. This faction is not averse to discussing politics, but tends to trot out the same few arguments about why less regulation has to be better. I wish I could blame this all on Ayn Rand, but a lot of it seems to come from people who have never heard of her. I suppose I could just add it to the bottom of the list of things I blame Reagan for.

To the first type of libertarian, I apologize for writing a FAQ attacking a caricature of your philosophy, but unfortunately that caricature is alive and well and posting smug slogans on Facebook.

0.3: Will this FAQ prove that government intervention always works better than the free market?

No, of course not.

Actually, in most cases, you won’t find me trying to make a positive proof of anything. I believe that deciding on, for example, an optimal taxation policy takes very many numbers and statistical models and other things which are well beyond the scope of this FAQ, and may well have different answers at different levels and in different areas.

What I want to do in most cases is not prove that the government works better than the free market, or vice versa, but to disprove theories that say we can be absolutely certain free market always works better than government before we even investigate the issue. After that, we may still find that this is indeed one of the cases where the free market works better than the government, but we will have to prove it instead of viewing it as self-evident from first principles.

0.4: Why write a Non-Libertarian FAQ? Isn’t statism a bigger problem than libertarianism?

Yes. But you never run into Stalinists at parties. At least not serious Stalinists over the age of twenty-five, and not the interesting type of parties. If I did, I guess I’d try to convince them not to be so statist, but the issue’s never come up.

But the world seems positively full of libertarians nowadays. And I see very few attempts to provide a complete critique of libertarian philosophy. There are a bunch of ad hoc critiques of specific positions: people arguing for socialist health care, people in favor of gun control. But one of the things that draws people to libertarianism is that it is a unified, harmonious system. Unlike the mix-and-match philosophies of the Democratic and Republican parties, libertarianism is coherent and sometimes even derived from first principles. The only way to convincingly talk someone out of libertarianism is to launch a challenge on the entire system.

There are a few existing documents trying to do this (see Mike Huben’s Critiques of Libertarianism and Mark Rosenfelder’s What’s (Still) Wrong With Libertarianism for two of the better ones), but I’m not satisfied with any of them. Some of them are good but incomplete. Others use things like social contract theory, which I find nonsensical and libertarians find repulsive. Or they have an overly rosy view of how consensual taxation is, which I don’t fall for and which libertarians definitely don’t fall for.

The main reason I’m writing this is that I encounter many libertarians, and I need a single document I can point to explaining why I don’t agree with them. The existing anti-libertarian documentation makes too many arguments I don’t agree with for me to feel really comfortable with it, so I’m writing this one myself. I don’t encounter too many Stalinists, so I don’t have this problem with them and I don’t see any need to write a rebuttal to their position.

If you really need a pro-libertarian FAQ to use on an overly statist friend, Google suggests The Libertarian FAQ.

0.5: How is this FAQ structured?

I’ve divided it into three main sections. The first addresses some very abstract principles of economics. They may not be directly relevant to politics, but since most libertarian philosophies start with abstract economic principles, a serious counterargument has to start there also. Fair warning: there are people who can discuss economics without it being INCREDIBLY MIND-NUMBINGLY BORING, but I am not one of them.

The second section deals with more concrete economic and political problems like the tax system, health care, and criminal justice.

The third section deals with moral issues, like whether it’s ever permissible to initiate force. Too often I find that if I can convince a libertarian that government regulation can be effective, they respond that it doesn’t matter because it’s morally repulsive, and then once I’ve finished convincing them it isn’t, they respond that it never works anyway. By having sections dedicated to both practical and moral issues, I hope to make that sort of bait-and-switch harder to achieve, and to allow libertarians to evaluate the moral and practical arguments against their position in whatever order they find appropriate.

Part A: Economic Issues

The Argument: In a free market, all trade has to be voluntary, so you will never agree to a trade unless it benefits you.

Further, you won’t make a trade unless you think it’s the best possible trade you can make. If you knew you could make a better one, you’d hold out for that. So trades in a free market are not only better than nothing, they’re also the best possible transaction you could make at that time. Labor is no different from any other commercial transaction in this respect. You won’t agree to a job unless it benefits you more than anything else you can do with your time, and your employer won’t hire you unless it benefits her more than anything else she can do with her money. So a voluntarily agreed labor contract must benefit both parties, and must do so more than any other alternative.

If every trade in a free market benefits both parties, then any time the government tries to restrict trade in some way, it must hurt both parties. Or, to put it another way, you can help someone by giving them more options, but you can’t help them by taking away options. And in a free market, where everyone starts with all options, all the government can do is take options away.

The Counterargument: This treats the world as a series of producer-consumer dyads instead of as a system in which every transaction affects everyone else. Also, it treats consumers as coherent entities who have specific variables like “utility” and “demand” and know exactly what they are, which doesn’t always work.

In the remainder of this section, I’ll be going over several ways the free market can fail and several ways a regulated market can overcome those failures. I’ll focus on four main things: externalities, coordination problems, irrational choice, and lack of information.

I did warn you it would be mind-numbingly boring.

1. Externalities

1.1: What is an externality?

An externality is when I make a trade with you, but it has some accidental effect on other people who weren’t involved in the trade.

Suppose for example that I sell my house to an amateur wasp farmer. Only he’s not a very good wasp farmer, so his wasps usually get loose and sting people all over the neighborhood every couple of days.

This trade between the wasp farmer and myself has benefited both of us, but it’s harmed people who weren’t consulted; namely, my neighbors, who are now locked indoors clutching cans of industrial-strength insect repellent. Although the trade was voluntary for both the wasp farmer and myself, it wasn’t voluntary for my neighbors.

Another example of externalities would be a widget factory that spews carcinogenic chemicals into the air. When I trade with the widget factory I’m benefiting – I get widgets – and they’re benefiting – they get money. But the people who breathe in the carcinogenic chemicals weren’t consulted in the trade.

1.2: But aren’t there are libertarian ways to solve externalities that don’t involve the use of force?

To some degree, yes. You can, for example, refuse to move into any neighborhood unless everyone in town has signed a contract agreeing not to raise wasps on their property.

But getting every single person in a town of thousands of people to sign a contract every time you think of something else you want banned might be a little difficult. More likely, you would want everyone in town to unanimously agree to a contract saying that certain things, which could be decided by some procedure requiring less than unanimity, could be banned from the neighborhood – sort of like the existing concept of neighborhood associations.

But convincing every single person in a town of thousands to join the neighborhood association would be near impossible, and all it would take would be a single holdout who starts raising wasps and all your work is useless. Better, perhaps, to start a new town on your own land with a pre-existing agreement that before you’re allowed to move in you must belong to the association and follow its rules. You could even collect dues from the members of this agreement to help pay for the people you’d need to enforce it.

But in this case, you’re not coming up with a clever libertarian way around government, you’re just reinventing the concept of government. There’s no difference between a town where to live there you have to agree to follow certain terms decided by association members following some procedure, pay dues, and suffer the consequences if you break the rules – and a regular town with a regular civic government.

As far as I know there is no loophole-free way to protect a community against externalities besides government and things that are functionally identical to it.

1.3: Couldn’t consumers boycott any company that causes externalities?

Only a small proportion of the people buying from a company will live near the company’s factory, so this assumes a colossal amount of both knowledge and altruism on the part of most consumers. See also the general discussion of why boycotts almost never solve problems in the next session.

1.4. What is the significance of externalities?

They justify some environmental, zoning, and property use regulations.

2. Coordination Problems

2.1: What are coordination problems?

Coordination problems are cases in which everyone agrees that a certain action would be best, but the free market cannot coordinate them into taking that action.

As a thought experiment, let’s consider aquaculture (fish farming) in a lake. Imagine a lake with a thousand identical fish farms owned by a thousand competing companies. Each fish farm earns a profit of $1000/month. For a while, all is well.

But each fish farm produces waste, which fouls the water in the lake. Let’s say each fish farm produces enough pollution to lower productivity in the lake by $1/month.

A thousand fish farms produce enough waste to lower productivity by $1000/month, meaning none of the fish farms are making any money. Capitalism to the rescue: someone invents a complex filtering system that removes waste products. It costs $300/month to operate. All fish farms voluntarily install it, the pollution ends, and the fish farms are now making a profit of $700/month – still a respectable sum.

But one farmer (let’s call him Steve) gets tired of spending the money to operate his filter. Now one fish farm worth of waste is polluting the lake, lowering productivity by $1. Steve earns $999 profit, and everyone else earns $699 profit.

Everyone else sees Steve is much more profitable than they are, because he’s not spending the maintenance costs on his filter. They disconnect their filters too.

Once four hundred people disconnect their filters, Steve is earning $600/month – less than he would be if he and everyone else had kept their filters on! And the poor virtuous filter users are only making $300. Steve goes around to everyone, saying “Wait! We all need to make a voluntary pact to use filters! Otherwise, everyone’s productivity goes down.”

Everyone agrees with him, and they all sign the Filter Pact, except one person who is sort of a jerk. Let’s call him Mike. Now everyone is back using filters again, except Mike. Mike earns $999/month, and everyone else earns $699/month. Slowly, people start thinking they too should be getting big bucks like Mike, and disconnect their filter for $300 extra profit…

A self-interested person never has any incentive to use a filter. A self-interested person has some incentive to sign a pact to make everyone use a filter, but in many cases has a stronger incentive to wait for everyone else to sign such a pact but opt out himself. This can lead to an undesirable equilibrium in which no one will sign such a pact.

The most profitable solution to this problem is for Steve to declare himself King of the Lake and threaten to initiate force against anyone who doesn’t use a filter. This regulatory solution leads to greater total productivity for the thousand fish farms than a free market could.

The classic libertarian solution to this problem is to try to find a way to privatize the shared resource (in this case, the lake). I intentionally chose aquaculture for this example because privatization doesn’t work. Even after the entire lake has been divided into parcels and sold to private landowners (waterowners?) the problem remains, since waste will spread from one parcel to another regardless of property boundaries.

2.1.1: Even without anyone declaring himself King of the Lake, the fish farmers would voluntarily agree to abide by the pact that benefits everyone.

Empirically, no. This situation happens with wild fisheries all the time. There’s some population of cod or salmon or something which will be self-sustaining as long as it’s not overfished. Fishermen come in and catch as many fish as they can, overfishing it. Environmentalists warn that the fishery is going to collapse. Fishermen find this worrying, but none of them want to fish less because then their competitors will just take up the slack. Then the fishery collapses and everyone goes out of business. The most famous example is the Collapse of the Northern Cod Fishery, but there are many others in various oceans, lakes, and rivers.

If not for resistance to government regulation, the Canadian governments could have set strict fishing quotas, and companies could still be profitably fishing the area today. Other fisheries that do have government-imposed quotas are much more successful.

2.1.2: I bet [extremely complex privatization scheme that takes into account the ability of cod to move across property boundaries and the migration patterns of cod and so on] could have saved the Atlantic cod too.

Maybe, but left to their own devices, cod fishermen never implemented or recommended that scheme. If we ban all government regulation in the environment, that won’t make fishermen suddenly start implementing complex privatization schemes that they’ve never implemented before. It will just make fishermen keep doing what they’re doing while tying the hands of the one organization that has a track record of actually solving this sort of problem in the real world.

2.2. How do coordination problems justify environmental regulations?

Consider the process of trying to stop global warming. If everyone believes in global warming and wants to stop it, it’s still not in any one person’s self-interest to be more environmentally conscious. After all, that would make a major impact on her quality of life, but a negligible difference to overall worldwide temperatures. If everyone acts only in their self-interest, then no one will act against global warming, even though stopping global warming is in everyone’s self-interest. However, everyone would support the institution of a government that uses force to make everyone more environmentally conscious.

Notice how well this explains reality. The government of every major country has publicly declared that they think solving global warming is a high priority, but every time they meet in Kyoto or Copenhagen or Bangkok for one of their big conferences, the developed countries would rather the developing countries shoulder the burden, the developing countries would rather the developed countries do the hard work, and so nothing ever gets done.

The same applies mutans mutandis to other environmental issues like the ozone layer, recycling, and anything else where one person cannot make a major difference but many people acting together can.

2.3: How do coordination problems justify regulation of ethical business practices?

The normal libertarian belief is that it is unnecessary for government to regulate ethical business practices. After all, if people object to something a business is doing, they will boycott that business, either incentivizing the business to change its ways, or driving them into well-deserved bankruptcy. And if people don’t object, then there’s no problem and the government shouldn’t intervene.

A close consideration of coordination problems demolishes this argument. Let’s say Wanda’s Widgets has one million customers. Each customer pays it $100 per year, for a total income of $100 million. Each customer prefers Wanda to her competitor Wayland, who charges $150 for widgets of equal quality. Now let’s say Wanda’s Widgets does some unspeakably horrible act which makes it $10 million per year, but offends every one of its million customers.

There is no incentive for a single customer to boycott Wanda’s Widgets. After all, that customer’s boycott will cost the customer $50 (she will have to switch to Wayland) and make an insignificant difference to Wanda (who is still earning $99,999,900 of her original hundred million). The customer takes significant inconvenience, and Wanda neither cares nor stops doing her unspeakably horrible act (after all, it’s giving her $10 million per year, and only losing her $100).

The only reason it would be in a customer’s interests to boycott is if she believed over a hundred thousand other customers would join her. In that case, the boycott would be costing Wanda more than the $10 million she gains from her unspeakably horrible act, and it’s now in her self-interest to stop committing the act. However, unless each boycotter believes 99,999 others will join her, she is inconveniencing herself for no benefit.

Furthermore, if a customer offended by Wanda’s actions believes 100,000 others will boycott Wanda, then it’s in the customer’s self-interest to “defect” from the boycott and buy Wanda’s products. After all, the customer will lose money if she buys Wayland’s more expensive widgets, and this is unnecessary – the 100,000 other boycotters will change Wanda’s mind with or without her participation.

This suggests a “market failure” of boycotts, which seems confirmed by experience. We know that, despite many companies doing very controversial things, there have been very few successful boycotts. Indeed, few boycotts, successful or otherwise, ever make the news, and the number of successful boycotts seems much less than the amount of outrage expressed at companies’ actions.

The existence of government regulation solves this problem nicely. If >51% of people disagree with Wanda’s unspeakably horrible act, they don’t need to waste time and money guessing how many of them will join in a boycott, and they don’t need to worry about being unable to conscript enough defectors to reach critical mass. They simply vote to pass a law banning the action.

2.3.1: I’m not convinced that it’s really that hard to get a boycott going. If people really object to something, they’ll start a boycott regardless of all that coordination problem stuff.

So, you’re boycotting Coke because they’re hiring local death squads to kidnap, torture, and murder union members and organizers in their sweatshops in Colombia, right?

Not a lot of people to whom I have asked this question have ever answered “yes”. Most of them had never heard of the abuses before. A few of them vaguely remembered having heard something about it, but dismissed it as “you know, multinational corporations do a lot of sketchy things.” I’ve only met one person who’s ever gone so far as to walk twenty feet further to get to the Pepsi vending machine.

If you went up to a random guy on the street and said “Hey, does hiring death squads to torture and kill Colombians who protest about terrible working conditions bother you?” 99.9% of people would say yes. So why the disconnect between words and actions? People could just be lying – they could say they cared so they sounded compassionate, but in reality it doesn’t really bother them.

But maybe it’s something more complicated. Perhaps they don’t have the brainpower to keep track of every single corporation that’s doing bad things and just how bad they are. Perhaps they’ve compartmentalized their lives and after they leave their Amnesty meetings it just doesn’t register that they should change their behaviour in the supermarket. Or perhaps the Coke = evil connection is too tenuous and against the brain’s ingrained laws of thought to stay relevant without expending extraordinary amounts of willpower. Or perhaps there’s some part of the subconscious that really is worry about that game theory and figuring it has no personal incentive to join the boycott.

And God forbid that it’s something more complicated than that. Imagine if the company that made the mining equipment that was bought by the mining company that mined the aluminum that was bought by Coke to make their cans was doing something unethical. You think you could convince enough people to boycott Coke that Coke would boycott the mining company that the mining company would boycott the equipment company that the equipment company would stop behaving unethically?

If we can’t trust people to stay off Coke when it uses death squads and when Pepsi tastes exactly the same (don’t argue with me on that one!) how can we assume people’s purchasing decisions will always act as a general moral regulatory method for the market?

2.3.2: And you really think governments can do better?

Sure seems that way. Many laws currently exist banning businesses from engaging in unethical practices. Some of these laws were passed by direct ballot. Others were passed by representatives who have incentives to usually follow the will of their constituents. So it seems fair to say that there are a lot of business practices that more than 51% of people thought should be banned.

But the very fact that a law was needed to ban them proves that those 51% of people weren’t able to organize a successful boycott. More than half of the population, sometimes much more, hated some practice so much they thought it should be illegal, yet that wasn’t enough to provide an incentive for the company to stop doing it until the law took effect.

To me, that confirms that boycotts are a very poor way of allowing people’s morals to influence corporate conduct.

2.4: How do coordination problems justify government spending on charitable causes?

Because failure to donate to a charitable cause might also be because of a coordination problem.

How many people want to end world hunger? I’ve never yet met someone who would answer with a “not me!”, but maybe some of those people are just trying to look good in front of other people, so let’s make a conservative estimate of 50%.

There’s a lot of dispute over what it would mean to “end world hunger”, all the way from “buy and ship food every day to everyone who is hungry that day” all the way to “create sustainable infrastructure and economic development such that everyone naturally produces enough food or money”. There are various estimates about how much these different definitions would cost, all the way from “about $15 billion a year” to “about $200 billion a year” – permanently in the case of shipping food, and for a decade or two in the case of promoting development.

Even if we take the highest possible estimate, it’s still well below what you would make if 50% of the population of the world donated $1/week to the cause. Now, certainly there are some very poor people in the world who couldn’t donate $1/week, but there are also some very rich people who could no doubt donate much, much more.

So we have two possibilities. Either the majority of people don’t care enough about world hunger to give a dollar a week to end it, or something else is going on.

That something else is a coordination problem. No one expects anyone else to donate a dollar a week, so they don’t either. And although somebody could shout very loudly “Hey, let’s all donate $1 a week to fight world hunger!” no one would expect anyone else to listen to that person, so they wouldn’t either.

When the government levies tax money on everyone in the country and then donates it to a charitable cause, it is often because everyone in the country supports that charitable cause but a private attempt to show that support would fall victim to coordination problems.

2.5: How do coordination problems justify labor unions and other labor regulation?

It is frequently proposed that workers and bosses are equal negotiating partners bargaining on equal terms, and only the excessive government intervention on the side of labor that makes the negotiating table unfair. After all, both need something from one another: the worker needs money, the boss labor. Both can end the deal if they don’t like the terms: the boss can fire the worker, or the worker can quit the boss. Both have other choices: the boss can choose a different employee, the worker can work for a different company. And yet, strange to behold, having proven the fundamental equality of workers and bosses, we find that everyone keeps acting as if bosses have the better end of the deal.

During interviews, the prospective employee is often nervous; the boss rarely is. The boss can ask all sorts of things like that the prospective pay for her own background check, or pee in a cup so the boss can test the urine for drugs; the prospective employee would think twice before daring make even so reasonable a request as a cup of coffee. Once the employee is hired, the boss may ask on a moment’s notice that she work a half hour longer or else she’s fired, and she may not dare to even complain. On the other hand, if she were to so much as ask to be allowed to start work thirty minutes later to get more sleep or else she’ll quit, she might well be laughed out of the company. A boss may, and very often does, yell at an employee who has made a minor mistake, telling her how stupid and worthless she is, but rarely could an employee get away with even politely mentioning the mistake of a boss, even if it is many times as unforgivable.

The naive economist who truly believes in the equal bargaining position of labor and capital would find all of these things very puzzling.

Let’s focus on the last issue; a boss berating an employee, versus an employee berating a boss. Maybe the boss has one hundred employees. Each of these employees only has one job. If the boss decides she dislikes an employee, she can drive her to quit and still be 99% as productive while she looks for a replacement; once the replacement is found, the company will go on exactly as smoothly as before.

But if the employee’s actions drive the boss to fire her, then she must be completely unemployed until such time as she finds a new job, suffering a long period of 0% productivity. Her new job may require a completely different life routine, including working different hours, learning different skills, or moving to an entirely new city. And because people often get promoted based on seniority, she probably won’t be as well paid or have as many opportunities as she did at her old company. And of course, there’s always the chance she won’t find another job at all, or will only find one in a much less tolerable field like fast food.

We previously proposed a symmetry between a boss firing a worker and a worker quitting a boss, but actually they could not be more different. For a boss to fire a worker is at most a minor inconvenience; for a worker to lose a job is a disaster. The Holmes-Rahe Stress Scale, a measure of the comparative stress level of different life events, puts being fired at 47 units, worse than the death of a close friend and nearly as bad as a jail term. Tellingly, “firing one of your employees” failed to make the scale.

This fundamental asymmetry gives capital the power to create more asymmetries in its favor. For example, bosses retain a level of control on workers even after they quit, because a worker may very well need a letter of reference from a previous boss to get a good job at a new company. On the other hand, a prospective employee who asked her prospective boss to produce letters of recommendation from her previous workers would be politely shown the door; we find even the image funny.

The proper level negotiating partner to a boss is not one worker, but all workers. If the boss lost all workers at once, then she would be at 0% productivity, the same as the worker who loses her job. Likewise, if all the workers approached the boss and said “We want to start a half hour later in the morning or we all quit”, they might receive the same attention as the boss who said “Work a half hour longer each day or you’re all fired”.

But getting all the workers together presents coordination problems. One worker has to be the first to speak up. But if one worker speaks up and doesn’t get immediate support from all the other workers, the boss can just fire that first worker as a troublemaker. Being the first worker to speak up has major costs – a good chance of being fired – but no benefits – all workers will benefit equally from revised policies no matter who the first worker to ask for them is.

Or, to look at it from the other angle, if only one worker sticks up for the boss, then intolerable conditions may well still get changed, but the boss will remember that one worker and maybe be more likely to promote her. So even someone who hates the boss’s policies has a strong selfish incentive to stick up for her.

The ability of workers to coordinate action without being threatened or fired for attempting to do so is the only thing that gives them any negotiating power at all, and is necessary for a healthy labor market. Although we can debate the specifics of exactly how much protection should be afforded each kind of coordination, the fundamental principle is sound.

2.5.1: But workers don’t need to coordinate. If working conditions are bad, people can just change jobs, and that would solve the bad conditions.

About three hundred Americans commit suicide for work-related reasons every year – this number doesn’t count those who attempt suicide but fail. The reasons cited by suicide notes, survivors and researchers investigating the phenomenon include on-the-job bullying, poor working conditions, unbearable hours, and fear of being fired.

I don’t claim to understand the thought processes that would drive someone to do this, but given the rarity and extremity of suicide, we can assume for every worker who goes ahead with suicide for work-related reasons, there are a hundred or a thousand who feel miserable but not quite suicidal.

If people are literally killing themselves because of bad working conditions, it’s safe to say that life is more complicated than the ideal world in which everyone who didn’t like their working conditions quits and get a better job elsewhere (see the next section, Irrationality).

I note in the same vein stories from the days before labor regulations when employers would ban workers from using the restroom on jobs with nine hour shifts, often ending in the workers wetting themselves. This seems like the sort of thing that provides so much humiliation to the workers, and so little benefit to the bosses, that a free market would eliminate it in a split second. But we know that it was a common policy in the 1910s and 1920s, and that factories with such policies never wanted for employees. The same is true of factories that literally locked their workers inside to prevent them from secretly using the restroom or going out for a smoking break, leading to disasters like the Triangle Shirtwaist Fire when hundreds of workers died when the building they were locked inside burnt down. And yet even after this fire, the practice of locking workers inside buildings only stopped when the government finally passed regulation against it.

3. Irrational Choices

3.1: What do you mean by “irrational choices”?

A company (Thaler, 2007, download study as .pdf) gives its employees the opportunity to sign up for a pension plan. They contribute a small amount of money each month, and the company will also contribute some money, and overall it ends up as a really good deal for the employees and gives them an excellent retirement fund. Only a small minority of the employees sign up.

The libertarian would answer that this is fine. Although some outsider might condescendingly declare it “a really good deal”, the employees are the most likely to understand their own unique financial situation. They may have a better pension plan somewhere else, or mistrust the company’s promises, or expect not to need much money in their own age. For some outsider to declare that they are wrong to avoid the pension plan, or worse to try to force them into it for their own good, would be the worst sort of arrogant paternalism, and an attack on the employees’ dignity as rational beings.

Then the company switches tactics. It automatically signs the employees up for the pension plan, but offers them the option to opt out. This time, only a small minority of the employees opt out.

That makes it very hard to spin the first condition as the employees rationally preferring not to participate in the pension plan, since the second condition reveals the opposite preference. It looks more like they just didn’t have the mental energy to think about it or go through the trouble of signing up. And in the latter condition, they didn’t have the mental energy to think about it or go through the trouble of opting out.

If the employees were rationally deciding whether or not to sign up, then some outsider regulating their decision would be a disaster. But if the employees are making demonstrably irrational choices because of a lack of mental energy, and if people do so consistently and predictably, then having someone else who has considered the issue in more depth regulate their choices could lead to a better outcome.

3.1.1: So what’s going on here?

Old-school economics assumed choice to be “revealed preference”: an individual’s choices will invariably correspond to their preferences, and imposing any other set of choices on them will result in fewer preferences being satisfied.

In some cases, economists have gone to absurd lengths to defend this model. For example, Bryan Caplan says that when drug addicts say they wish that they could quit drugs, they must be lying, since they haven’t done so. Seemingly unsuccessful attempts to quit must be elaborate theater, done to convince other people to continue supporting them, while they secretly enjoy their drugs as much as ever.

But the past fifty years of cognitive science have thoroughly demolished this “revealed preference” assumption, showing that people’s choices result from a complex mix of external compulsions, internal motivations, natural biases, and impulsive behaviors. These decisions usually approximate fulfilling preferences, but sometimes they fail in predictable and consistent ways.

The field built upon these insights is called “behavioral economics”, and you can find more information in books like Judgment Under Uncertainty, Cognitive Illusions, and Predictably Irrational, or on the website Less Wrong.

3.2: Why does this matter?

The gist of this research, as it relates to the current topic, is that people don’t always make the best choice according to their preferences. Sometimes they consistently make the easiest or the most superficially attractive choice instead. It may be best not to think of them as a “choice” at all, but as a reflexive reaction to certain circumstances, which often but not always conforms to rationality.

Such possibilities cast doubt on the principle that every trade that can be voluntarily made should be voluntarily made.

If people’s decisions are not randomly irrational, but systematically irrational in predictable ways, that raises the possibility that people who are aware of these irrationalities may be able to do better than the average person in particular fields where the irrationalities are more common, raising the possibility that paternalism can sometimes be justified.

3.2.1: Why should the government protect people from their own irrational choices?

By definition of “irrational”, people will be happier and have more of their preferences satisfied if they do not make irrational choices. By the principles of the free market, as people make more rational decisions the economy will also improve.

If you mean this question in a moral sense, more like “How dare the government presume to protect me from my own irrational choices!”, see the section on Moral Issues.

3.2.2: What is the significance of predictably irrational behavior?

It justifies government-mandated pensions, some consumer safety and labor regulations, advertising regulations, concern about addictive drugs, and public health promotion, among other things.

4. Lack of Information

4.1: What do you mean by “lack of information”?

Many economic theories start with the assumption that everyone has perfect information about everything. For example, if a company’s products are unsafe, these economic theories assume consumers know the product is unsafe, and so will buy less of it.

No economist literally believes consumers have perfect information, but there are still strong arguments for keeping the “perfect information” assumption. These revolve around the idea that consumers will be motivated to pursue information about things that are important to them. For example, if they care about product safety, they will fund investigations into product safety, or only buy products that have been certified safe by some credible third party. The only case in which a consumer would buy something without information on it is if the consumer had no interest in the information, or wasn’t willing to pay as much for the information as it would cost, in which case the consumer doesn’t care much about the information anyway, and it is a success rather than a failure of the market that it has not given it to her.

In nonlibertarian thought, people care so much about things like product safety and efficacy, or the ethics of how a product is produced, that the government needs to ensure them. In libertarian thought, if people really care about product safety, efficacy and ethics, the market will ensure them itself, and if they genuinely don’t care, that’s okay too.

4.1.1: And what’s wrong with the libertarian position here?

Section 5 describes how we can sometimes predict when people will make irrational choices. One of the most consistent irrational choices people make is buying products without spending as much effort to gather information as the amount they care about these things would suggest. So in fact, the nonlibertarians are right: if there were no government regulation, people who care a lot about things like safety and efficacy would consistently be stuck with unsafe and ineffective products, and the market would not correct these failures.

4.2. Is this really true? Surely people would investigate the safety, ethics, and efficacy of the products they buy.

Below follows a list of statements about products. Some are real, others are made up. Can you identify which are which?

- Some processed food items, including most Kraft cheese products, contain methylarachinate, an additive which causes a dangerous anaphylactic reaction in 1/31000 people who consume it. They have been banned in Canada, but continue to be used in the United States after intense lobbying from food industry interests.

- Commonly used US-manufactured wood products, including almost all plywood, contain formaldehyde, a compound known to cause cancer. This has been known in scientific circles for years, but was only officially reported a few months ago because of intense chemical industry lobbying to keep it secret. Formaldehyde-containing wood products are illegal in the EU and most other developed nations.

- Total S.A., an oil company that owns fill-up stations around the world, sometimes uses slave labor in repressive third-world countries to build its pipelines and oil wells. Laborers are coerced to work for the company by juntas funded by the corporation, and are shot or tortured if they refuse. The company also helps pay for the military muscle needed to keep the juntas in power.

- Microsoft has cooperated with the Chinese government by turning over records from the Chinese equivalents of its search engine “Bing” and its hotmail email service, despite knowing these records would be used to arrest dissidents. At least three dissidents were arrested based on the information and are currently believed to be in jail or “re-education” centers.

- Wellpoint, the second largest US health care company, has a long record of refusing to provide expensive health care treatments promised in some of its plans by arguing that their customers have violated the “small print” of the terms of agreement; in fact they make it so technical that almost all customers violate them unknowingly, then only cite the ones who need expensive treatment. Although it has been sued for these practices at least twice, both times it has used its legal muscle to tie the cases up in court long enough that the patients settled for an undisclosed amount believed to be fraction of the original benefits promised.

- Ultrasonic mosquito repellents like those made by GSI, which claim to mimic frequencies produced by the mosquito’s natural predator, the bat, do not actually repel mosquitoes. Studies have shown that exactly as many mosquitoes inhabit the vicinity of such a mosquito repellent as anywhere else.

- Listerine (and related mouth washes) probably do not eliminate bad breath. Although it may be effective at first, in the long term it generally increases bad breath by drying out the mouth and inhibiting the salivary glands. This may also increase the population of dental bacteria. Most top dentists recommend avoiding mouth wash or using it very sparingly.

- The most popular laundry detergents, including most varieties of Tide and Method, have minimal to zero ability to remove stains from clothing. They mostly just makes clothing smell better when removed from the laundry. Some of the more expensive alkylbenzenesulfonate detergents have genuine stain-removing action, but aside from the cost, these detergents have very strong smells and are unpopular.

4.2.1. Okay, I admit I’m not sure of most of these. What’s your point?

This is a complicated FAQ about complicated philosophical issues. Most likely its readers are in the top few percentiles in terms of intelligence and education.

And we live in a world where there are many organizations, both private and governmental, that exist to evaluate products and disseminate information about their safety.

And all of the companies and products above are popular ones that most American consumers have encountered and had to make purchasing decisions about. I tried to choose safety issues that were extremely serious and carried significant risks of death, and ethical issues involving slavery and communism, which would be of particular importance to libertarians.

If the test was challenging, it means that the smartest and best-educated people in a world full of consumer safety and education organizations don’t bother to look up important life-or-death facts specifically tailored to be relevant to them about the most popular products and companies they use every day.

And if that’s the case, why would you believe that less well-educated people in a world with less consumer safety information trying to draw finer distinctions between more obscure products will definitely seek out the consumer information necessary allows them to avoid unsafe, unethical, or ineffective products?

The above test is an attempt at experimental proof that people don’t seek out even the product information that is genuinely important to them, but instead take the easy choice of buying whatever’s convenient based on information they get from advertising campaigns and the like.

4.2.2: Fine, fine, what are the answers to the test?

Four of them are true and four of them are false, but I’m not saying which are which, in the hopes that people will observe their own thought processes when deciding whether or not it’s worth looking up.

4.2.3: Right, well of course people don’t look up product information now because the government regulates that for them. In a real libertarian society, they would be more proactive.

All of the four true items on the test above are true in spite of government regulation. Clearly, there are still significant issues even in a regulated environment.

If you honestly believe you have no incentive to look up product information because you trust the government to take care of that, then you’re about ten times more statist than I am, and I’m the guy writing the Non-Libertarian FAQ.

4.3: What other unexpected consequences might occur without consumer regulation?

It could destroy small business.

In the absence of government regulation, you would have to trust corporate self-interest to regulate quality. And to some degree you can do that. Wal-Mart and Target are both big enough and important enough that if they sold tainted products, it would make it into the newspaper, there would be a big outcry, and they would be forced to stop. One could feel quite safe shopping at Wal-Mart.

But suppose on the way to Wal-Mart, you see a random mom-and-pop store that looks interesting. What do you know about its safety standards? Nothing. If they sold tainted or defective products, it would be unlikely to make the news; if it were a small enough store, it might not even make the Internet. Although you expect the CEO of Wal-Mart to be a reasonable man who understands his own self-interest and who would enforce strict safety standards, you have no idea whether the owner of the mom-and-pop store is stupid, lazy, or just assumes (with some justification) that no one will ever notice his misdeeds. So you avoid the unknown quantity and head to Wal-Mart, which you know is safe.

Repeated across a million people in a thousand cities, big businesses get bigger and small businesses get unsustainable.

4.4: What is the significance of lack of information?

It justifies some consumer and safety regulations, and the taxes necessary to pay for them.

Part B: Social Issues

The Argument: Those who work hardest (and smartest) should get the most money. Not only should we not begrudge them that money, but we should thank them for the good they must have done for the world in order to satisfy so many consumers.

People who do not work hard should not get as much money. If they want more money, they should work harder. Getting more money without working harder or smarter is unfair, and indicative of a false sense of entitlement.

Unfortunately, modern liberal society has internalized the opposite principle: that those who work hardest are greedy people who must have stolen from those who work less hard, and that we should distrust them at until they give most of their ill-gotten gains away to others. The “progressive” taxation system as it currently exists serves this purpose.

This way of thinking is not only morally wrong-headed, but economically catastrophic. Leaving wealth in the hands of the rich would “make the pie bigger”, allowing the extra wealth to “trickle down” to the poor naturally.

The Counterargument: Hard work and intelligence are contributory factors to success, but depending on the way you phrase the question, you find you need other factors to explain between one-half and nine-tenths of the difference in success within the United States; within the world at large the numbers are much higher.

If we think factors other than hard work and intelligence determining success are “unfair”, then most of Americans’ life experiences are determined by “unfair” factors.

Although it would be overly ambitious to want to completely eliminate all unfairness, we know that most other developed countries have successfully eliminated many of the most glaring types of unfairness, and reaped benefits greater than the costs from doing so.

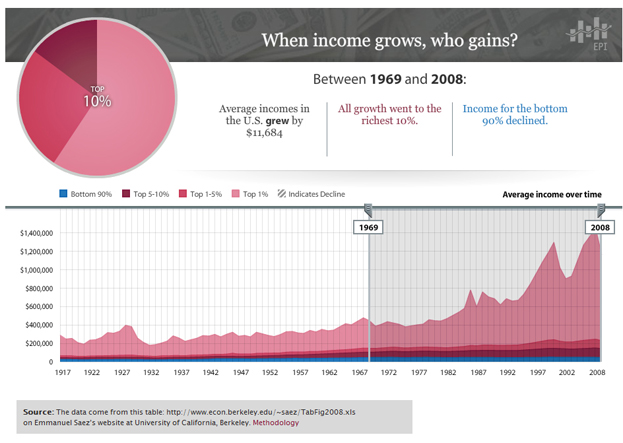

The progressive tax system is part of this policy of eliminating unfairness, but if you disagree with that, that’s okay, as more and more of the country’s wealth is staying in the hands of the super-rich. None of this wealth has trickled down to the poor and none of it ever will, as the past thirty years of economic history have repeatedly and decisively demolished the “trickle-down” concept.

None of this implies that any particular rich person is “greedy”, whatever that would mean.

5. Just Deserts and Social Mobility

5.1: Government is the recourse of “moochers”, who want to take the money of productive people and give it to the poor. But rich people earned their money, and poor people had the chance to earn money but did not. Therefore, the poor do not deserve rich people’s money.

The claim of many libertarians is that the wealthy earned their money by the sweat of their brow, and the poor are poor because they did not. The counterclaim of many liberals is that the wealthy gained their wealth by various unfair advantages, and that the poor never had a chance. These two conflicting worldviews have been the crux of many an Internet flamewar.

Luckily, this is an empirical question, and can be solved simply by collecting the relevant data. For example, we could examine whether the children of rich parents are more likely to be rich than poor parents, and, if so, how much more likely they are. This would give us a pretty good estimate of how much of rich people’s wealth comes from superior personal qualities, as opposed to starting with more advantages.

If we define “rich” as “income in the top 5%” and “poor” as “income in the bottom 5%” then children of rich parents are about twenty times more likely to become rich themselves than children of poor parents.

But maybe that’s an extreme case. Instead let’s talk about “upper class” (top 20%) and “lower class” (bottom 20%). A person born to a lower-class family only has a fifty-fifty chance of ever breaking out of the lower class (as opposed to 80% expected by chance), and only about a 3% chance of ending up in the upper class (as opposed to 20% expected by chance). The children of upper class parents are six times more likely to end up in the upper class than the lower class; the children of lower class families are four times more likely to end up in the lower class than the upper class.

The most precise way to measure this question is via a statistic called “intergenerational income mobility”, which studies have estimated at between 0.4 and 0.6. This means that around half the difference in people’s wealth, maybe more, can be explained solely by who their parents are.

Once you add in all the other factors besides how hard you work – like where you live (the average Delawarean earns $30000; the average Mississippian $15000) and the quality of your local school district, there doesn’t seem to be much room for hard work to determine more than about a third of the difference between income.

5.1.1: The conventional wisdom among libertarians is completely different. I’ve heard of a study saying that people in the lower class are more likely to end up in the upper class than stay in the lower class, even over a period as short as ten years!

First of all, note that this is insane. Since the total must add up to 100%, this would mean that starting off poor actually makes you more likely to end up rich than someone who didn’t start off poor. If this were true, we should all send our children to school in the ghetto to maximize their life chances. This should be a red flag.

And, in fact, it is false. Most of the claims of this sort come from a single discredited study. The study focused on a cohort with a median age of twenty-two, then watched them for ten years, then compared the (thirty-two-year-old) origins with twenty-two-year-olds, then claimed that the fact that young professionals make more than college students was a fact about social mobility. It was kind of weird.

Why would someone do this? Far be it from me to point fingers, but Glenn Hubbard, the guy who conducted the study, worked for a conservative think tank called the “American Enterprise Institute”. You can see a more complete criticism of the study here.

5.1.2: Okay, I acknowledge that at least half of the differences in wealth can be explained by parents. But that needn’t be rich parents leaving trust funds to their children. It could also be parents simply teaching their children better life habits. It could even be genes for intelligence and hard work.

This may explain a small part of the issue, but see 5.1.3 and 5.1.3.1, which show that under different socioeconomic conditions, this number markedly decreases. These socioeconomic changes would not be expected to affect things like genetics.

5.1.3: So maybe children of the rich do have better opportunities, but that’s life. Some people just start with advantages not available to others. There’s no point in trying to use Big Government to regulate away something that’s part of the human condition.

This lack of social mobility isn’t part of the human condition, it’s a uniquely American problem. Of eleven developed countries investigated in a recent study on income mobility, America came out tenth out of eleven. Their calculation of US intergenerational income elasticity (the number previously cited as probably between 0.4 and 0.6) was 0.47. But other countries in the study had income elasticity as low as 0.15 (Denmark), 0.16 (Australia), 0.17 (Norway), and 0.19 (Canada). In each of those countries, the overwhelming majority of wealth is earned by hard work rather than inherited.

The United States, is just particularly bad at this; the American Dream turns out to be the “nearly every developed country except America” Dream.

Studies show that increasing government spending significantly improves social mobility. States with higher government spending have about 33% more social mobility than states with lower spending.

This also helps explain why other First World countries have better social mobility than we do. Poor American children have very few chances to go to Harvard or Yale; poor Canadian children have a much better chance to go to to UToronto or McGill, where most of their tuition is government-subsidized.

5.2: Then perhaps it is true that rich children start out with a major unfair advantage. But this advantage can be overcome. Poor children may have to work harder than rich children to become rich adults, but this is still possible, and so it is still true, in the important sense, that if you are not rich it’s mostly your own fault.

Several years ago, I had an interesting discussion with an evangelical Christian on the ethics of justification by faith. I promise you this will be relevant eventually.

I argued that it is unfair for God to restrict entry to Heaven to Christians alone. After all, 99% of native-born Ecuadorans are Christian, but less than 1% of native born Saudis are same. It follows that the chance of any native-born Ecuadorian of becoming Christian is 99%, and that of any native born Saudi, 1%. So if God judges people by their religion, then within 1% He’s basically just decided it’s free entry for Ecuadorians, but people born in Saudi Arabia can go to hell (literally).

My Christian friend argued that is not so: that there is a great difference between 0% of Saudis and 1% of Saudis. I answered that no, there was a 1% difference. But he said this 1% proves that the Saudis had free will: that even though all the cards were stacked against them, a few rare Saudis could still choose Christianity.

But what does it mean to have free will, if external circumstances can make 99% of people with free will decide one way in Ecuador, and the opposite way in Saudi Arabia?

I do sort of believe in free will, or at least in “free will”. But where my friend’s free will was unidirectional, an arrow pointing from MIND to WORLD, my idea of free will is circular: MIND affects WORLD affects MIND affects WORLD and so on.

Yes, it is ultimately the mind and nothing else that decides whether to accept or reject Islam or Christianity. But it is the world that shapes the mind before it does its accepting or rejecting. A man raised in Saudi Arabia uses a mind forged by Saudi culture to make the decision, and chooses Islam. A woman raised in Ecuador uses a mind forged by Ecuador to make the decision, and chooses Christianity. And so there is no contradiction in the saying that the decision between Islam and Christianity is up entirely to the individual, yet that it is almost entirely culturally determined. For the mind is a box, filled with genes and ideas, and although it is a wonderful magical box that can take things and combine them and forge them into something quite different and unexpected, it is not infinitely magical, and it cannot create out of thin air.

Returning to the question at hand, every poor person has the opportunity to work hard and eventually become rich. Whether that poor person grasps the opportunity comes from that person’s own personality. And that person’s own personality derives eventually from factors outside that person’s control. A clear look at the matter proves it must be so, or else personality would be self-created, like the story of the young man who received a gift of a time machine from a mysterious aged stranger, spent his life exploring past and future, and, in his own age, goes back and gives his time machine to his younger self.

5.2.1: And why is this relevant to politics?

Earlier, I offered a number between 0.4 and 0.6 as the proportion of success attributable solely to one’s parents’ social class. This bears on, but does not wholly answer, a related question: what percentage of my success is my own, and what percentage is attributable to society? People have given answers to this question as diverse as (100%, 0%), (50%, 50%), (0%, 100%).

I boldly propose a different sort of answer: (80%, 100%). Most of my success comes from my own hard work, and all of my own hard work comes from external factors.

If all of our success comes from external factors, then it is reasonable to ask that we “pay it forward” by trying to improve the external factors of others, turning them into better people who will be better able to seize the opportunities to succeed. This is a good deal of the justification for the liberal program of redistribution of wealth and government aid to the poor.

5.2.2: This is all very philosophical. Can you give some concrete examples?

Lead poisoning, for example. It’s relatively common among children in poorer areas (about 7% US prevalence) and was even more common before lead paint and leaded gasoline was banned (still >30% in many developing countries).

For every extra ten millionths of a gram per deciliter concentration of lead in their blood, children permanently lose five IQ points; there’s a difference of about ten IQ points among children who grew up in areas with no lead at all, and those who grew up in areas with the highest level of lead currently considered “safe”. Although no studies have been done on severely lead poisoned children from the era of leaded gasoline, they may have lost twenty or more IQ points from chronic lead exposure.

Further, lead also decreases behavioral inhibition, attention, and self-control. For every ten ug/dl lead increase, children were 50% more likely to have recognized behavioral problems. People exposed to higher levels of blood lead as a child were almost 50% more likely to be arrested for criminal behavior as adults (adjusting for confounders).

Economic success requires self-control, intelligence, and attention. It is cruel to blame people for not seizing opportunities to rise above their background when that background has damaged the very organ responsible for seizing opportunities. And this is why government action, despite a chorus of complaints from libertarians, banned lead from most products, a decision which is (controversially) credited with the most significant global drop in crime rates in decades, but which has certainly contributed to social mobility and opportunity for children who would otherwise be too lead-poisoned to succeed.

Lead is an interesting case because it has obvious neurological effects preventing success. The ability of psychologically and socially toxic environments to prevent success is harder to measure but no less real.

If a poor person can’t keep a job solely because she was lead-poisoned from birth until age 16, is it still fair to blame her for her failure? And is it still so unthinkable to take a little bit of money from everyone who was lucky enough to grow up in an area without lead poisoning, and use it to help her and detoxify her neighborhood?

5.3: What is the significance of whether success is personally or environmentally determined?

It provides justification for redistribution of wealth, and for engineering an environment in which more people are able to succeed.

6. Taxation

6.1: Isn’t taxation, the act of taking other people’s money by force, inherently evil?

See the Moral Issues section for a more complete discussion of this point.

6.2: Isn’t progressive taxation, the tendency to tax the rich at higher rates than the poor, unfair?

The most important justification for progressive tax rates is the idea of marginal utility.

This is easier to explain with movie tickets than money. Suppose different people are allotted a different number of non-transferable movie tickets for a year; some people get only one, other people get ten thousand.

A person with only two movie ticket might love to have one extra ticket. Perhaps she is a huge fan of X-Men, Batman, and Superman, and with only two movie ticket she will only be able to see two of the three movies she’s super-excited about this year.

A person with ten movie tickets would get less value from an extra ticket. She can already see the ten movies that year she’s most interested in. If she got an eleventh, she’d use it for a movie she might find a bit enjoyable, but it wouldn’t be one of her favorites.

A person with a hundred movie tickets would get minimal value from an extra ticket. Even if your tickets are free, you’re not likely to go to the movies a hundred times a year. And even if you did, you’d start scraping the bottom of the barrel in terms of watchable films.

A person with a thousand tickets would get practically no value from an extra ticket. At this point,t here’s no way she can go to any more movies. The extra ticket might not have literally zero value – she could burn it for warmth, or write memos on the back of it – but it’s pretty worthless.

So although all movie tickets provide an equal service – seeing one movie – one extra movie ticket represents a different amount of value to the person with two tickets and the person with a thousand tickets. Furthermore, 50% of their movie ticket holdings represent a different value to the person with two tickets and the person with a thousand movie tickets. The person with two tickets loses the ability to watch the second-best film of the year. The person with a thousand tickets still has five hundred tickets left, more than enough to see all the year’s best films, and at worst will have to buy some real memo paper.

Money works similarly to movie tickets. Your first hundred dollars determine whether you live or starve to death. Your next five hundred dollars determine whether you have a roof over your head or you’re freezing out on the street. But by your ten billionth dollar, all you’re doing is buying a slightly larger yacht.

50% of what a person with $10,000 makes is more valuable to her than 50% of what a billionaire makes is to the billionaire.

Progressive taxation is an attempt to tax everyone equally, not by lump sum or by percentage, but by burden. Just as taking extra movie tickets away from the person with a thousand is more fair than taking some away from the person with only two, so we tax the rich at a higher rate because a proportionate amount of money has less marginal value to them.

6.2.1: But the progressive tax system is unfair and perverse. Imagine the tax rate on people making $100,000 or less is 30%, and the tax rate on people making more than $100,000 is 50%. You make $100,000, and end up with after tax income of $70,000. Then one day your boss tells you that you did a good job, and gives you a $1 bonus. Now you make $100,001, but end up with only $50,000.50 after tax income. How is that at all fair?

It’s not, but this isn’t how the tax system works.

What those figures mean is that your first $100,000, no matter how much you earn, is taxed at 30%. Then the money you make after that is taxed at 50%. So if you made $100,001, you would be taxed 30% on the first $100,000 (giving you $70,000), and 50% on the next $1 (giving you $.50), for an after-tax income of $70,000.50. The intuitive progression where someone who makes more money ends up with more after-tax income is preserved.

I know most libertarians don’t make this mistake, and that there are much stronger arguments against progressive taxation, but this has come up enough times that I thought it was worth mentioning, with apologies to those readers whose time it has wasted.

6.3: Taxes are too high.

Too high by what standard?

6.3.1: Too high by historical standards. Thanks to the unstoppable growth of big government, people have to pay more taxes now than ever before.

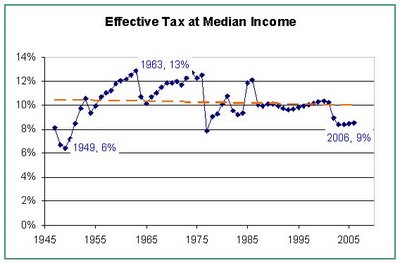

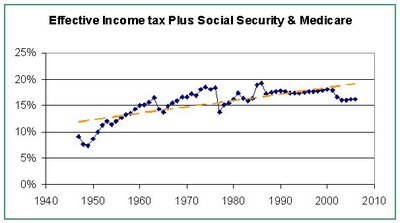

Actually, income tax rates for people on median income are around the lowest they’ve been in the past seventy-five years

Actually, income tax rates for the rich are around the lowest they’ve been in the past seventy-five years.

This is true. As the rich get richer and the poor get poorer (see 3.4), more of the money concentrates in the hands of the rich, and so more of the taxes come from the rich as well. This doesn’t contradict the point that the tax rates on the rich are near historic lows.

Actually, income tax rates for corporations are around the lowest they’ve been in the past seventy-five years.

6.3.2: I meant income taxes are too high compared to what’s best for the economy, and even best for the Treasury. With taxes as high as they are, people will stop producing, rather than see so much of each dollar they make go to the government. This will hurt the economy and lower tax revenue.

The Laffer curve certainly exists, but the consensus is that we’re still well on the left half of it.

Although it’s become a truism that high tax rates discourage production, studies have found this to be mostly false, with low elasticity of real income – see for example Gruber & Saez and Saez, Slemrod, and Giertz.

What studies have found is a high elasticity of taxable income. That is, raising taxes encourages people to find more tax loopholes, decreasing revenue. However, although this effect means a 10% higher tax rate would lead to less than 10% higher government income, the change in government income would still be positive – even by this stricter criterion, we’re still on the left side of the Laffer curve. And of course, this effect could be eliminated by switching to a flat tax or closing tax loopholes.

6.4: Our current tax system is overzealous in its attempts to redistribute money from the rich to the poor. If instead we lowered taxes on the rich, this money would “trickle down” to the rest of the economy, driving growth. Instead of redistributing the pie, we’d make the pie larger for everyone.

If we’re in an overzealous campaign for “equality” intended to lower the rich to the level of the poor, we’re certainly not doing a very good job of it. Over the past thirty years, the rich have consistently gotten richer. None of this money has trickled down to the poor or middle-class, whose income has remained the same in real terms.

“Trickle-down” should be rejected as an interesting and plausible-sounding economic theory which empirical data have soundly disconfirmed.

6.5: Raising taxes would be useless for the important things like cutting the deficit. The deficit is $1.2 trillion. The most we could realistically raise from extra taxes on the rich would be maybe $200 billion. The most we could raise from insane levels of extra taxes on the rich and middle class would be about $500 billion – less than half the deficit. The real problem is spending.

Yes and no.

The deficit is, indeed, very, very large. It’s so large that no politically palatable option is likely to make more than a small dent in it. This is true of tax increases. It’s also true of spending cuts.

Cutting all redistributive government services for the poor including welfare, unemployment insurance, disability, food stamps, scholarships, you name it – would save about $200 billion. That’s less than 20% of the deficit. Cutting all health care, including Medicaid for senior citizens, would only eliminate $400 billion or so. Even eliminating the entire military down to the last Jeep would only get us $800 billion or so. The targets for cuts that have actually been raised are rounding errors: the Republicans trumpeted an end for government aid to NPR, but this is about $4 million – all of 0.000003% of the problem.

So “darnit, this one thing doesn’t completely solve the deficit” is not a good reason to reject a proposal. Solving the deficit will, if it’s possible at all, take a lot of different methods, including some unpalatable to liberals, some unpalatable to conservatives, and yes, some unpalatable to libertarians.

In particular, we need to avoid the “bee sting” fallacy, where we have so many problems that we just stop worrying. It would be irresponsible to say that since a few billion dollars doesn’t affect the deficit either way, we might as well just spend $5 billion on some random project we don’t need. For the same reason, it would be irresponsible to say we might as well just renew tax cuts on the rich that cost hundreds of billions of dollars each year.

6.6. Taxes are basically a racket where they take my money and then give it to foreign governments and poor people.

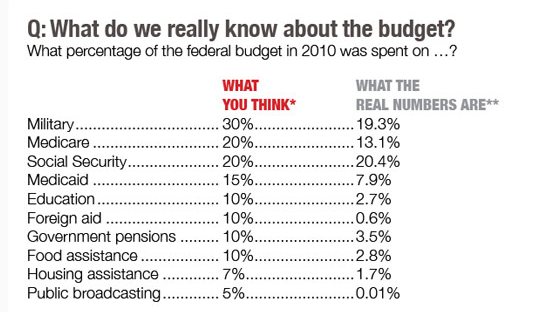

According to a CNN poll, on average Americans estimate that about 10% of our taxes go to foreign aid. The real number is about 0.6%.

And although people believe that food and housing for the poor take up about 20% of the federal budget, the real number is actually less than 5%.

So although people worry that 30% of the budget goes to help the less fortunate, the real number is about 6%.

(And this is actually sort of depressing, when you think about it.)

The majority of your taxes go to programs that benefit you and other middle-class Americans, such as Social Security and Medicare, and to programs that “benefit” you and other middle-class Americans, such as the military.

Part C: Political Issues

The Argument: Government can’t do anything right. Its forays into every field are tinged in failure. Whether it’s trying to create contradictory “state owned businesses”, funding pet projects that end up over budget and useless, or creating burdensome and ridiculous “consumer protection” rules, its heavy-handed actions are always detrimental and usually embarrassing.

With this track record, what sane person would want to involve government in even more industries? The push to get government deeper into health care is a disaster waiting to happen, and could give us a chronically broken system like those in Europe, where people die because of bureaucratic inefficiency.

Other places from which we can profitably eliminate government’s prying hands include our schools, our prisons, our gun dealerships, and the friendly neighborhood meth lab.

The Counterargument: Government sometimes, though by no means always, does things right, and some of its institutions and programs are justifiably considered models of efficiency and human ingenuity. There are various reasons why people are less likely to notice these.

Government-run health systems empirically produce better health outcomes for less money than privately-run health systems for reasons that include economies of scale. There are a mountain of statistics that prove this. Although not every proposal to introduce government into health will necessarily be successful, we would do well to consider emulating more successful systems.

We should think twice about exactly how much government we are willing to remove from our schools, gun dealerships, and meth labs, and run away screaming at the proposal to privatize prisons.

7. Competence of Government

7.1: Government never does anything right.

7.1.1: Okay, fine. But that’s a special case where, given an infinite budget, they were able to accomplish something that private industry had no incentive to try. And to their credit, they did pull it off, but do you have any examples of government succeeding at anything more practical?

Eradicating smallpox and polio globally, and cholera and malaria from their endemic areas in the US. Inventing the computer, mouse, digital camera, and email. Building the information superhighway and the regular superhighway. Delivering clean, practically-free water and cheap on-the-grid electricity across an entire continent. Forcing integration and leading the struggle for civil rights. Setting up the Global Positioning System. Ensuring accurate disaster forecasts for hurricanes, volcanoes, and tidal waves. Zero life-savings-destroying bank runs in eighty years. Inventing nuclear power and the game theory necessary to avoid destroying the world with it.

Brought peace. But see also Government Success Stories and The Forgotten Achievements of Government.

7.2: Large government projects are always late and over-budget.

The only study on the subject I could find, “What Causes Cost Overrun in Transport Infrastructure Projects?” ( download study as .pdf) by Flyvbjerg, Holm, and Buhl, finds no difference in cost overruns between comparable government and private projects, and in fact find one of their two classes of government project (those not associated with a state-owned enterprise) to have a trend toward being more efficient than comparable private projects. They conclude that “…one conclusion is clear… the conventional wisdom, which holds that public ownership is problematic whereas private ownership is a main source of efficiency in curbing cost escalation, is dubious.”